The Talent Paradox: Why Most First Finance Hires Are NGMI

By Chris Fenster, Founder & Executive Chairman

“Diana” was one of the best first finance hires I’d seen a client make in years. She had more than a decade of progressive finance experience across four companies—including two blue-chip industry leaders, and two emerging firms small enough that I knew she could handle the hands-on work.

Sometimes first hires see Propeller as a threat, but not Diana. She was both confident and competent: a good partner and manager to our accounting team, checking in regularly to ask for advice or give me a heads up about what she was thinking.

Eighteen months later, Diana was gone.

The founder reached out to me a few months before her departure to tell me they just needed someone with more … horsepower. I had a call with Diana to try to convince her to stay under a new CFO (I thought a couple of years working for a “real” CFO would be a great career accelerator.) But it was clear she was hoping to get the title herself and wasn’t willing to be “layered.”

The company went through two more finance leaders over the next 18 months before bringing in an experienced CFO. By that time, it was well into nine-figure revenue and had become one of the fastest-growing companies we’d ever seen.

The Feature That Should Be a Bug

I wish I could say this was an exception, but this pattern has repeated itself with alarming frequency in our most successful clients—so much so, that I coach founders to plan for it. Over the last 17 years, Propeller has worked with 22 companies that reached unicorn valuations: different products and different founders, but remarkably similar finance leadership journeys.

The pattern goes like this. Somewhere between $25-50M in revenue, the company hires a Head of Finance who feels perfect. This leader builds key systems and makes themselves indispensable. Then, 12-24 months later, they’re out.

What’s happening is a talent paradox: the more you optimize a finance hire for one specific stage, the less likely they are to succeed at the next stage.

This isn’t a talent problem; it’s a stage mismatch problem. Fast-growing companies have vastly different needs at different stages. It’s a symptom of hyper-performance that wouldn’t be nearly as disruptive if founders saw it coming and planned for it.

To be clear: this is a hyper-growth problem. Companies that grow from $20M to $100M in 24 months evolve faster than almost anyone can learn—especially when you’re also building the plane while flying it. Companies growing at normal rates (20-30% annually) give their finance leaders time to build skills alongside the business. But at 50-100%+ growth rates—the kind we’ve seen across our 22 unicorns—the job changes faster than most people can adapt. It’s not about talent; it’s about velocity.

This paradox is particularly acute in finance. At various points, a finance leader needs technical rigor (building systems from scratch), strategic vision (guiding capital allocation), operational discipline (scaling processes), and communication skills (working with boards and investors). This combination is rare, and anyone who has all these skills is almost by definition incapable of successfully executing in earlier stages that optimize for speed over quality.

What Companies Need in Finance Leadership at Each Stage

To understand why this pattern repeats, it’s helpful to look at what’s required at each growth stage. Drawing on insights from a16z partner Jeff Jordan and BenchBoard’s Jim Cook, here’s what each stage actually requires.

Launch Stage ($0-5M): The Builder

Most companies won’t make it past this stage, so you need to focus on your product and customers and just stay out of trouble. This means building “minimum viable accounting”: hiring a bookkeeping firm, and maybe that college roommate who works at an investment bank, to help you raise money.

The critical skill here isn’t sophistication: it’s scrappiness and speed. You will be accumulating systems and data debt, which means you aren’t saving as much money as you think; instead, you’re deferring it. You’re going to pay later in cleanup work and perhaps sooner, in poor decision-making due to cloudy visibility.

Traction Stage ($5-25M): The Translator

At this point most firms have their first institutional capital, and with that, surplus confidence and a discipline deficit. Diana was hired into the tail end of this phase.

Here you need a systems thinker who can plan 18-24 months ahead. This is the time to professionalize and set up “80/20” solutions: systems and controls that deliver most of what you’ll need for the next few years without breaking the bank.

Nearly everything you build at this stage will get replaced in the next two stages, but that’s fine—the company is going to change everything anyhow, and spending 10X for enterprise systems that have 1/10th the flexibility is a waste of the most expensive capital you’ll ever raise.

At this stage, you need a “translator”: someone who can earn the trust of founders, understand their vision, and translate it into a financial model, unit economics, and fundraising strategy, while building “scrappy GAAP” accounting. Your next fundraise will be based on cold, hard data.

And here’s where companies make their first big mistake: they hire someone they call a “CFO” when what they really need is a strong Director or VP.

The person you can actually afford and attract at $20M is overqualified for 50% of the work and underqualified for the most critical 25%.

Think about what Diana was doing: 50% accounting, basic reporting and closing books (overqualified), 25% building systems, forecasting and managing the team (her sweet spot), and 25% strategic planning and board storytelling (underqualified). She’s a “tweener”: too senior for half the work, too junior for the most critical quarter. But the “CFO” title set expectations she couldn’t meet.

Awkward Stage ($25-50M): The Truth-Teller

This is where finance gets real. Some of the best companies have “uh-oh” moments here when they realize none of this is as easy as they thought. Sometimes customers disappear. Other times they can’t make product fast enough, and every distribution channel adds less gross profit. Things you “fixed” less than a year ago are breaking again.

Whether you’re underperforming or overperforming, you have less money than you thought, so there’s not yet budget to fix what’s breaking. And surprise: your board wants an audit before your Series C.

This is where the resourceful generalist you hired to professionalize becomes, in Secret CFO’s words, a “controller in CFO clothing.” You need a truth-teller who can tell you that you need to make changes and back it up with data.

The fancy Excel models and systems you put in are revealed to be woefully inadequate. Controllers specialize in forensics, but you need someone who knows how to build foresight: someone who can be both a forensic detective and a decision architect. They need to own the business model, define your path to profitability, and manage the cash burn multiple that investors care about.

A finance leader who can’t surface uncomfortable truths won’t survive this stage. As Jim Cook notes, “You will be fired as CFO 80% of the time based on bad behaviors vs. your lack of functional capabilities.”

Scale Stage ($50-100M+): The Architect

Somewhere between $50M and $100M it becomes obvious you’re going to return capital, and investors back up truckloads of cash for an enterprise-grade shopping spree. Experienced “mid-market” professionals get hired to replace perfectly-competent-but-barely-keeping-up leaders. Everything matters now. Every 30 basis points per year of inefficiency at this revenue velocity could buy a Lambo.

Almost nothing the Awkward CFO built survives this level of discipline and control, so the Scale CFO needs to be an architect and communicator who can design systemic controls and analytics to replace the good-enough versions that were all you could afford before.

This is someone you can trust to provide objective guidance about all the things your new execs are telling you that you need to do. At Scale, you need someone who can tell your financial story to multiple audiences, negotiate with sophisticated investors, and align cross-functional leaders around strategic priorities.

This financial leadership framework isn’t controversial. The mystery is why growing companies’ financial transitions still fail so predictably. The answer lies in the psychological journey leaders take through these stages.

The Confidence Curve: Diana’s Journey

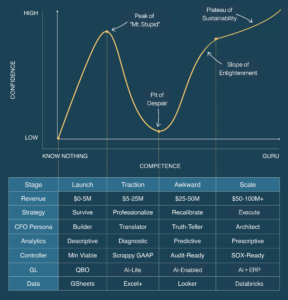

If you’re familiar with the Dunning-Kruger effect, you know the shape of this curve: people overestimate their competence early and underestimate it later. In finance hiring, this plays out in a particularly tricky way.

At Launch ($0-5M): The Rebound

Founders start below zero: after 50 investor rejections, confidence is crushed. But once they get funding and achieve product-market fit, confidence rebounds sharply into “Know-Nothing” mode. Few things hemorrhage confidence like hearing “no” from 50 investors. Raising capital catapults your confidence into the clouds, and this is actually useful to the extent that it helps you move fast without overthinking things.

At Traction ($5-25M): Peak Confidence

Diana came in at this stage, around $18M in revenue. The books started closing faster, forecasts got cleaner, and investors were impressed. Everything she built worked. This is the “Peak of Mt. Stupid”, but that’s not an insult: it’s appropriate confidence! The problems at this stage should be solved with speed and execution. Diana was exactly what the company needed. For 18 months, she was the hero.

At Awkward ($25-50M): Valley of Despair

Here’s what the CEO saw: Diana became “gun-shy”: hesitant, asking more questions than she answered, less decisive. What he interpreted as declining performance was actually Diana recognizing the gaps in what she’d built.

The forecasting models that worked at $18M couldn’t capture the new complexity. The team she’d assembled didn’t have the strategic thinking needed for horizon planning. The clean answers she used to deliver now came with caveats and uncertainty.

Diana wasn’t failing. The job had changed underneath her.

The systems she built were perfect for $5-25M. They were breaking at $30M not because Diana made mistakes, but because $30M requires different systems. And Diana—being smart and self-aware—could see this. Her hesitation wasn’t incompetence; it was wisdom.

But here’s the deeper problem: Diana had the title “CFO.” When the company actually needed a CFO at Scale, there was no graceful path forward.

At Scale ($50-100M+): Plateau of Sustainability

The new CFO came in with battle scars from previous companies. She’d been through this transition before. She knew what audit-ready looked like, what investors expected, and how to build systems that could scale. She arrived at the “Plateau of Sustainability” because she’d already climbed this mountain somewhere else.

But she also spent her first six months doing archaeology: trying to reverse-engineer why decisions were made the way they were. Diana was gone, and with her went critical institutional knowledge.

Why Companies Keep Making the Same Mistake

The Title Trap

Great Scale-stage CFOs understand something crucial: they look at a $20M company and think, “I’d be overqualified for 50% of the work, underqualified for the most critical 25%, and setting myself up to either be bored or ineffective.” So they wait. They take roles where the complexity matches their capabilities.

This creates a structural problem: the person you can afford at $20M isn’t a CFO in the eyes of someone who’s been a CFO at $100M. But companies give them the “CFO” title anyway. When the company hits $50M and actually needs CFO-level strategic work, everyone’s stuck.

The Optionality Play

The smarter approach: hire for optionality. At the Awkward stage ($25-50M), hire a VP Finance whom you explicitly inform that they might be layered at $75M+. Give them two paths: grow into a future CFO role with support, or offramp into a firm growing at a pace they can manage. This signals to future CFOs: “We were clear-eyed about what the job actually is at different stages.”

The Confidence Valley

You find a great person who matches all your criteria, and you want so badly to believe they’ll be different from the pattern. Plus, investors and boards want accountability in the form of a single person.

It’s all about the confidence curve: success at Awkward comes from doing (rolling up your sleeves, building things yourself). Success at Scale comes from designing (creating systems, delegating deeply, thinking two steps ahead). These are fundamentally different psychological profiles. Asking someone to stop doing what made them successful is like asking a surgeon to become a hospital CEO.

The Real Cost

Most founders respond to the talent paradox in one of two ways: they wait too long to upgrade because of loyalty, or they churn through finance leaders trying to find the “perfect” hire (spoiler: it doesn’t exist across all stages).

Both approaches are expensive. The first costs you in missed opportunities and scaling pain. The second costs you in institutional knowledge and continuity.

Context is everything in finance. Your historical financial story—the decisions you made, the systems you built, the metrics you tracked—is the fabric of success when you’re trying to scale efficiently. Every time you swap out your finance function entirely, you lose a thread. Diana’s company lost a lot of momentum by cycling through three finance leaders.

If You’re a First Finance Hire Reading This

You’re not the problem. The smartest first finance hires understand this pattern and plan for it. You have three options:

- Build with scaffolding. Partner with an embedded team that fills your blind spots and gives you pattern recognition from hundreds of companies. You grow into the role because you’re not doing it alone.

- Position as foundation, not forever. Take a VP Finance title (not “CFO”) with explicit understanding you might thrive with the coaching of a scale CFO. Two years learning from a world-class CFO beats struggling alone in a role you’re not ready for.

- Time your exit strategically. If you’re thriving at the Traction stage, that’s your superpower. Becoming a serial “first finance hire” who professionalizes early-stage companies is a legitimate, lucrative career path.

The trap is taking a “CFO” title at $20M and believing you should grow into a $100M CFO role on your own. The complexity curve is too steep, and the Dunning-Kruger effect makes it worse. Diana wasn’t failing when she left—she was recognizing a mismatch early enough to land somewhere she could thrive.

A Different Approach: Continuity + Strategic W2 Hires

This is exactly why we built Propeller the way we did.

At Launch/Traction ($0-25M):

You don’t need a W2 VP Finance yet. You need an embedded team that can build scrappy systems, professionalize the basics, and prepare you for institutional capital—without the overhead of a senior hire you can’t yet afford or effectively utilize.

At Awkward ($25-50M):

This is when you hire your VP Finance (not “CFO”): someone who understands they might be layered at Scale. Here, Propeller shifts from leading to supporting: we become the scaffolding that helps your VP Finance succeed. We provide pattern recognition from hundreds of companies, we fill gaps in their experience, and we give them a bench to draw from.

At Scale ($50-100M+):

You hire your Architect CFO. But instead of six months of archaeology, they inherit functioning systems, institutional knowledge, and a capable VP of Finance who can run day-to-day operations. Propeller continues providing specialized support where needed, but your W2 team is driving.

The key insight: it’s not Propeller instead of W2 hires. It’s Propeller + strategically-timed W2 hires = continuity through transitions.

We maintain the collective knowledge of your financial journey. We’re not starting from scratch every 18 months, or trying to reverse-engineer decisions made before the new CFO arrived, because we were there.

You Hired Right, for the Wrong Stage

Remember Diana? After she left that role, she landed at a company perfectly matched to her Awkward-stage expertise. She thrived there, building the systems and accountability frameworks that made her excellent in the first place. The company that “outgrew” her didn’t hire wrong; they hired right for the wrong stage.

The talent paradox isn’t a failure of hiring; it’s a feature of growth. Companies evolve faster than individuals, especially in specialized functions like finance. The question isn’t whether you’ll outgrow your finance team’s capabilities; it’s whether you’ll have the continuity and institutional knowledge to navigate those transitions smoothly.

The truth is, there is no perfect hire. There’s only the right support at the right time, with the wisdom of where you’ve been to inform where you’re going.

Want to explore how Propeller can grow with your business through every stage? Let’s talk.